African Oil Palm & African Rice

Elia Nurvista and Rubiane Maia exchange artistic research processes that bring them into closer proximity with the politics of plants, labour, and ecologies that produce our most common food stuffs and comodities; rice and palm oil. Each fosters long term research that considers the ways lives are enmeshed in the oppressions of the plantations and considers artistic methods to rekindle other relations with plants.

Elia Nurvista, African Oil Palm

I am interested to see palm oil closely, not only because Indonesia, the country where I am from, is known as the biggest producer of palm oil, but also because we are so distant from this plant and the plantation, even when we consume it everyday. I have never been to a palm oil plantation, though my father came from Kalimantan island, home of a massive plantation. Still, I have used countless products containing palm oil for my daily consumption, consciously or not.

Palm oil or Elaeis guineensis is a native plant from West Africa. In the 15th century the Europeans “discovered” the usefulness of these plants and brought them to Europe through slavery. But long before that African people already had the knowledge to process it into oil, wine, medicine, for firing, and fiber. By the seventeenth century, palm oil was commonly available as medicine in England, and by the late eighteenth century palm oil became a staple ingredient in soap and candles during the Industrial Revolution.

The story of the first palm oil tree in Southeast Asia began some time before with four seedlings that came to Java’s Buitenzorg (now Bogor) botanical gardens in 1848 from Bourbon, Mauritius via Amsterdam. But it wasn’t the success story of palm oil as a fruitful industrial crop yet. It takes around 40 years of trial and error by European scientists to find the best formula for this plant to be a perfect commodity, from the soils, seeds and pollinators. Long story short, in 1911 the first big scale plantation was born in Deli Sumatra, the predecessor for the ultimate and unstoppable monoculture plantation in Indonesia.

Rubiane Maia, African Rice

Through the lens of my Book-Performance project (a series of performance based on autobiographical texts started in 2018), I followed the rice on its fantastic story of migration in the hair of African women during the transatlantic slave trade.

Despite finding more information about North American plantations, my focus was on Brazil, where I was born and where rice is one of the main foods. Opting for artistic research that went beyond studying and reading, I wrote and performed a new text, titled ’The tongue bends whenever it faces what is unquestionable or what has been cursed’, chapter VI at the 35th São Paulo Biennial. During the presentation I embodied important aspects of care and healing connected to the tongue and language, highlighting many contradictions in historical and botanical narratives in the colonial centuries.

Soon after, I had the opportunity to visit for the first time a rice plantation in Japan, getting closer to rice seeds and plants. Recently, ‘Becoming Rice’ turned into the title of this expanding research, which has no predicted ending.

-

Correspondence

Rubiane: I found your statement about being distant from Palm Oil plants and plantations very interesting, even though we are active consumers. I’ve been thinking exactly the same thing about rice. Could you share more thoughts on this? Have you been thinking about strategies to get closer? How do you relate to plants?

Elia: Indeed, as I read the omnipresent headline in popular media that Indonesia and Malaysia together are the biggest producers for global palm oil without the majority of us knowing what is happening or how it can be happened, historically and politically. Like I mentioned, I, as many other Indonesian people, have never been to a plantation and many people here know the products of palm oil are merely cooking oil. There was a moment when the scarcity of cooking oil happened because of the hoarding of cooking oil supply by cartels, and instead of learning more about palm oil industry from up to downstream, the masses blamed the government who didn’t fight for the grassroots’ which is also understandable.

So, I assume most of us also didn’t know what the palm oil fruit looks like, in what kind of condition; environment and labor it’s being cultivated and what is the next process to become the products we consume daily. It might be because geographically the location of the plantation existed on another island outside Java. Java is a prominent island where all economically, socially and the culture of Indonesia centralized there. It seems the process of palm oil from cultivating into refineries is disconnected from Java and the global sphere.

Thinking about getting closer with this issue, the huge world of palm oil industries in Indonesia generates awareness which is dominated by the knowledge of agribusiness, such as how to be a good plantation owner with a very productives harvest, or how to be a good worker in this business. Meanwhile, through my project, I want to emphasize ecological justice behind this agroindustry, to learn more about what was happening in the field and how the local people have a relation to this plant, which is so complex. Often we only hear about the orangutans who were expelled because of deforestation, which this issue mostly comes from western NGO such WWF and so on. On the other hand there is discourse on how this agribusiness brings huge benefits in the economy to build the nation, without telling the consequences of ecologies including the labor, local and indigenous people who are affected and the uncontrolled transformation of their life in very extractive ways. Those two dominating news need to be balanced with a more critical perspective. There is already a lot of academic research examining this from the ethnography, sociology and anthropology disciplines but oftenly their thoughts only distribute in a limited group of people. Social and art projects can be one of a way to disseminate and be a platform to rethink in broader audiences, even though it is slow but I think worth being tried.

So the important thing for me is not only to get closer with the issue, but to have more critical and reflection on how this extractive industry becomes part of our daily life and how the complex situation lies for people who often don’t have a choice.

Rubiane: In Brazil, my country of origin, we are stuck with the monoculture of transgenic soybeans instead of palm oil for the production of cooking oil. I think this has kept palm oil popularly called ‘dendê oil’ as a special and ritualistic ingredient in northeastern Afro-Brazilian cuisine. It was only recently that I became aware of the problems related to the huge cultivation of this plant. So, I am quite curious about the different uses of palm oil in different contexts, mainly in Asia and Africa. Did you discover anything that you found particularly interesting about the uses of Elaeis guineensis? Does your research have a focus? Or, did it gain a focus throughout its development?

Elia: When I learned about the history of palm oil plantations in Indonesia, I was a bit surprised that the plant is not endemic to Indonesia or even Asia. It’s from west Africa. That’s also why we don’t have recipes or gastronomy using red palm oil, because when it came to Indonesia (at that time Dutch East Indies) was only as industrial crops. In Indonesia we don’t know how to process it using hands on a household scale. I didn’t find Indonesian food and recipes using unrefined palm oil, which is so common in African cuisine.

It’s fascinating what you said on “dendê oil’ as a special and ritualistic ingredient in northeastern Afro-Brazilian cuisine. I didn’t realize that Brazil also uses red unrefined palm oil until my Brazilian friend showed me her ingredients in her kitchen. Then I am connecting on how the history of Afro Brazilian,

But it’s interesting that some housewives here accidentally found mushrooms growing in a pile of palm fruit dregs after it gets pressed. So , they try to consume the mushrooms and its edible and taste good, and later try cultivating and selling it in the market. It’s called jamur tankos (jamur = mushroom and tankos = the palm oil dregs). Even though right now I don’t have any focus on that, it can be an interesting way to develop.

Rubiane: What stage of research are you at now? Did you develop any artistic responses through this process? Do you intend to continue working with palm oil? What are you planning for the future?

Elia: I started learning about the extraction of palm oil cultivation and production while learning and working together with the groups of Indigenous people in Indonesia such as ‘Talang Mamak’ in Sumatra and ‘Paser’ in Kalimantan who struggled from the plantation. Through my platform Struggles for Sovereignty, they shared and exchanged their strategy on how to face the massive plantation, which we can learn together from several cases. Unfortunately my plan to visit them is still not yet realized and until now i don’t have an opportunity to do so, but i am still planning.

I have been continuing the research project for my post-academic in Jan van Eyck, Netherlands within the framework of how palm oil is being circulated and consumed, mostly in the Global North context. I formed the palm oil study group with three other colleagues and did desk research on the history of palm oil plantation in Indonesia which was introduced by Dutch Colonial, into the present consumer with ethical movement, and the NGOs which are concerned with the ecology, environment and labor issues in Europe. Within this research, I sense though the concern about ecology is rooted in the same problem of devastation, nevertheless there are different realities which can lead to disconnected and moreover patronizing ways to tackle this problem. It’s urgent for me to understand how palm oil as a global commodity seems detached; not only from its processing from crude to end products. Yet the discourse of ecological and social justice behind it, between the site of production and where it consumes seems disengaged.

Last year I was continuing my research in Nantes, France as part of research fellows at Institut the Advanced Study de Nantes. In this period I was exploring public policies focused in the EU regarding the palm oil trade. One of my starting points was prompted when the media brought up the “Nutella tax” in France, in which the French senate added tax on foods manufactured with palm oil due the ecological devastations caused by this industry. At the same time, these well-intentioned initiatives inflict immediate and undermine consequences on oil palm industry countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, that currently generate employment for some five million farmers which depend on this economy. This ambivalence shows how complex global food systems and their repercussions on different localities. Recently I am interested in how the palm oil industry is connected in global trade, such as the refineries and the invisible investment behind this which I am still thinking and reflecting on how to examine this issue, how to start and what kind of methodology etc.

Along with my palm oil research since the first chapter, I have produced several forms such as videos, sculptures, prints, and textile works as part of my object based installation. Apart from that I also formed the study collective, workshops, reading group, and event based format to share my thoughts regarding this project, under the title ‘Long Hanging Fruits’. I think this project will continue for the next few years as I found there are still many things to explore and learn surrounding this topic. I like the way that i kept going through and detoured to many chapters to understand this complex commodity.

Elia: What are the most interesting aspects that motivate you when you do the research about rice?

Rubiane: Initially I felt quite motivated by the story of rice migration to the Americas. Like most Brazilians, I grew up eating rice and beans every day, being taught that these are the two most important foods to have on our plate every day. As Brazil is the country outside of Asia with the highest rate of rice production and consumption in the world, it seemed fascinating to me to look deeper into the historical issues surrounding rice plant. I think the simple idea that the seeds smuggled during the period of the transatlantic crossing were persistently cultivated into entire plantations, which sustained the colony’s subsistence for a long period, seemed fascinating to me.

There are many contradictions between the official history and oral history about rice cultivation in the colonial period. Complex questions about how the two species of rice, Oryza sativa (Asian rice) and Oryza glaberrima (African rice) were developed across the continents. It is impressive how effective colonial logic was in restricting access to knowledge about certain plants, as in the case of glaberrima, for a long time it was discriminated against in botanical classifications as a wild variation of sativa. Another aspect that has brought me a lot of motivation is thinking about the memory of plants. In the case of glaberrima, could we talk about the existence of a plant memory that encompasses the trauma of slavery? I don’t have an answer for that, but I like to believe so, that plants carry their own history in their DNA, and that somehow this can be accessed, felt, processed, transferred.

Elia: What kind of methodology did you apply when you did research about rice? And how’s your process from this research turned into artistic formats?

Rubiane: For me, it is always important to consider the context in which my research is inserted to think about a methodology. It took me a while to choose which plant to follow, but from the beginning, I was decided to opt for a plant that was a food. Later, I found myself fascinated by the story that rice migrated to the Americas hidden in the hair of enslaved women and children during the transatlantic crossing. For several weeks I couldn’t get this image out of my head: hair and rice. I started reading articles and theses about the history of rice in the Americas, especially in Brazil and at the same time I began to study the processes of plant domestication and migration. Thus I began to understand the differentiation between the two species Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima. So, without realising it, I had already started following the rice.

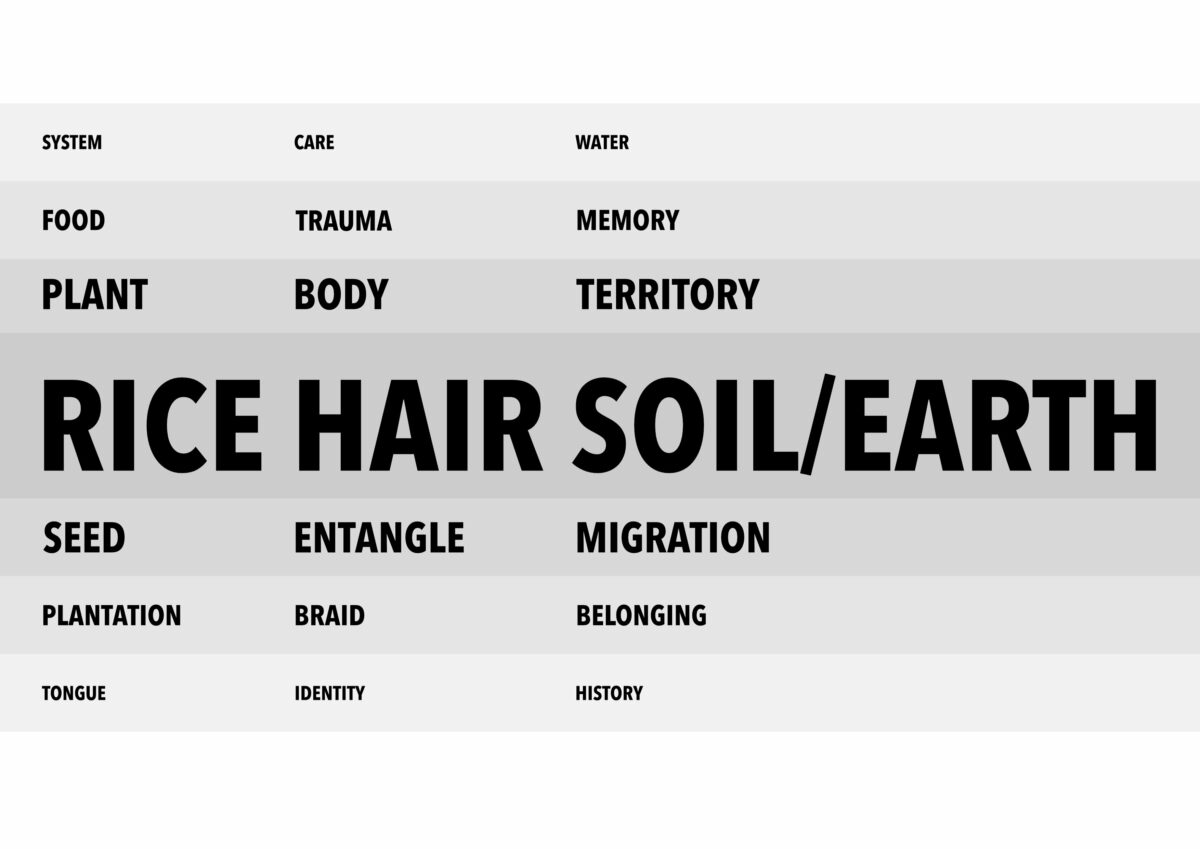

At the same time, as I was about to start developing a new Chapter (VI) of the Book-Performance project, a series of performative actions in response to autobiographical texts to be presented at the 35th São Paulo Biennial ‘Choreography of the Impossible’. Besides just following the rice, I thought it would be interesting to share my research in a performative way. As the Book- Performance demands the creation of a dense and disruptive text connected with memory I thought I should use the tongue as a guiding element in writing, since it encompasses both the relationship we have with food and language. The entire content of the text is intertwined with the relationship between rice, hair, soil and tongue/language. To be more precise, I created a simple diagram where I multiply the key words into concepts. This exercise helped me bring more tangible elements to the writing.

When the text began to take shape, I began to develop the action that I should present along with it. I decided to build a large glass reservoir with soil and water, like a large puddle of muddy water, in which I would enter to touch the soil while hiding rice seeds in my hair and mouth. The action should take place simultaneously with the reading of my text being performed by another black woman in front of a microphone.

I also had the opportunity to visit a rice plantation in Japan. I had never been to a rice plantation before, and it was very special. It was a relatively small farmland, managed by a group of families. Everyone was there for the harvest, from the oldest to the youngest, including some children and a mother with a baby. Rice is grown for their own consumption, so they organised harvest day as a kind of festive ritual. Just as you mention, I also thought a lot about the distance between what we consume and plants, plantations. So, it seemed a little surreal to me to have grown up in a country that is one of the largest rice producers in the world, and never to have seen a rice plant. Seeing a rice plantation was a desire from the beginning, but it was a part of the research that I couldn’t predict. This was an extremely important experience for me. Stepping barefoot on the muddy, watery ground, touching and cutting the bushes, seeing the greenish seeds before they dry, tying and hanging the piles, being together with all group of people, even with a strong language barrier. They were all dressed in blue with indigo-dyed clothes, as one of the families has an indigo plantation very close by, which I went to visit later.

Elia: How do you see the potential possibilities in the future of this research ? Do you have any plans or ideas regarding cross-disciplinary or experimenting new formats?

Rubiane: I feel that the research on/with rice does not have time to end, as it is so vast. There are several aspects that I have not delved into, such as genetic modifications, commodity relations, gender issues that are associated with the cultivation of rice plantations and the study of plant memory itself, which is something that interests me a lot. As my artistic practice is very interdisciplinary, I see a lot of potential for expansion into different media and formats. I still don’t have anything concrete for the future, but as I’m currently carrying out research on soil and mineral pigments, I’ve been getting closer and closer to the matter. So, it would be interesting to give space to new creations that are not centred just on performance.

Since I started following rice, I’ve been collecting my own hair. In November I ended up doing another performance called ‘Solid Ground’ in which I create clay balls with rice and my hair inside. The result ended up becoming a sculpture with balls in different sizes intertwined by a rope.