Amaranth & Prickly Pear

Keg de Souza and Mariana Martínez Balvanera’s research engages with plants that are entangled in and shaped by colonial disruptions. Mariana follows varieties of the chenopodium or goosefoot plant that were found and domesticated all over the world while Keg researches the prickly pear or ‘nopal’ that were displaced from Mexico by colonial vegetal economies and were co-opted as biological forms of enclosure in their new territories.

Mariana Martínez Balvanera, Amaranth

Amaranth, one of the oldest American domesticated plants, captivated my interest when I worked in Oaxaca and Xochimilco’s ancient milpas. Amaranth is part of a group of wild and domesticated plants known in Mexico as Quelites. Even though they used to be a dominant crop for the indigenous people (alongside corn), during colonial times the settler Spaniards banned Amaranth (Huauhtli) after witnessing Aztec rituals involving Amaranth sculptures used in goddess Huitzilopochtli’s veneration. The ban stemmed from Amaranth’s association with rituals, nutrition and sovereignty, and its status as a “weed” rather than an edible and spiritual crop in the newly colonized country.

Quelites (edible wild greens) grow within and around the milpa and are used in different Mexican recipes like tamales and soups, recipes that I have learned from traditional cooks and close relatives. Quelite Cenizo, Quintonil, Huauzontle, Quelite Gigante are all wild greens that are related to Amaranth (Amaranthae family) by their genus Chenopodium. Some of these plants can also be found growing in plots and sidewalks of cities outside of Mexico. They are plants that grow almost anywhere in the world. These resilient, ubiquitous plants that grow in diverse locations, symbolize rebellion and dispersion. I have found in them a nostalgic link to my culture when I spot them abroad, and this is the reason why I chose to research the entangled meanings and pasts of these spiritual rebel plants.

Keg de Souza, Prickly Pear

I have been researching the colonial entanglements of Australia (where I live as a settler) and India (my ancestral lands) through the movement of particular plants. One such plant is the prickly pear, native to the Americas, it was sent out by the British to the colonial outposts of Australia and India to create a habitat for the cochineal insect. When crushed, cochineal insects create a deep red dye, at the time it was used to colour the robes of royalty, cardinals and the British military redcoats: to mask the colour of blood.

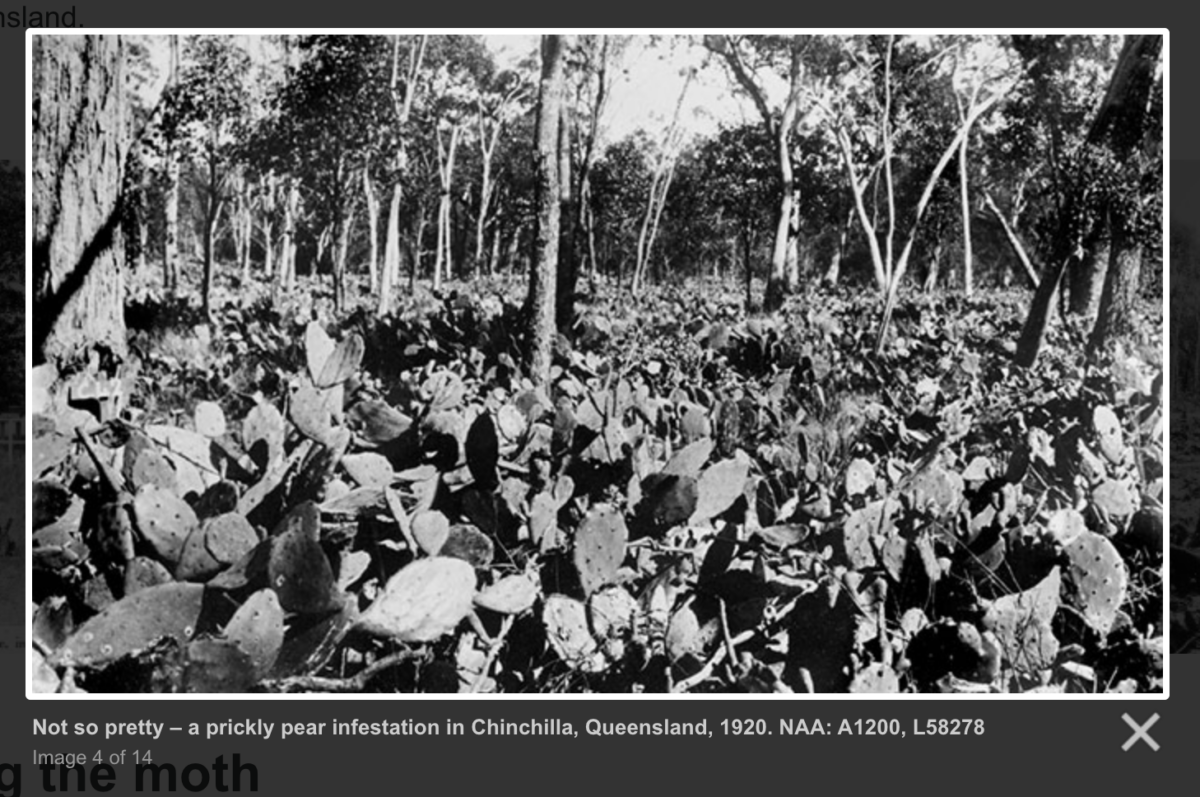

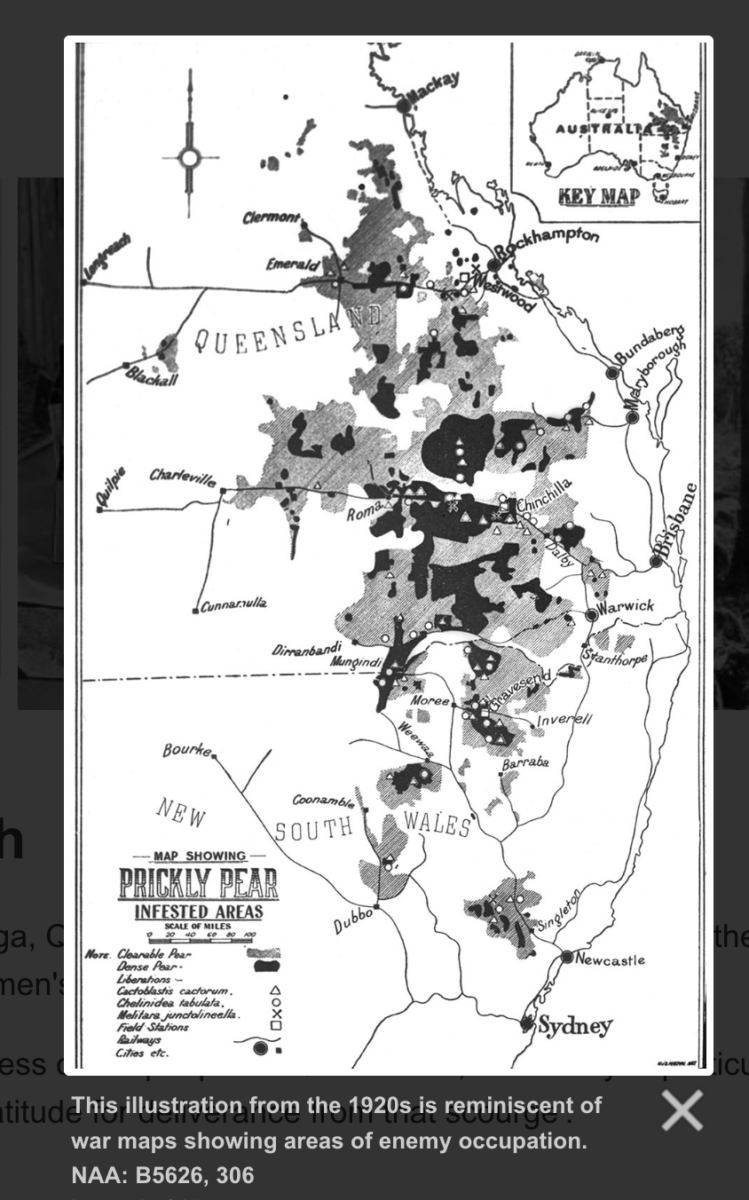

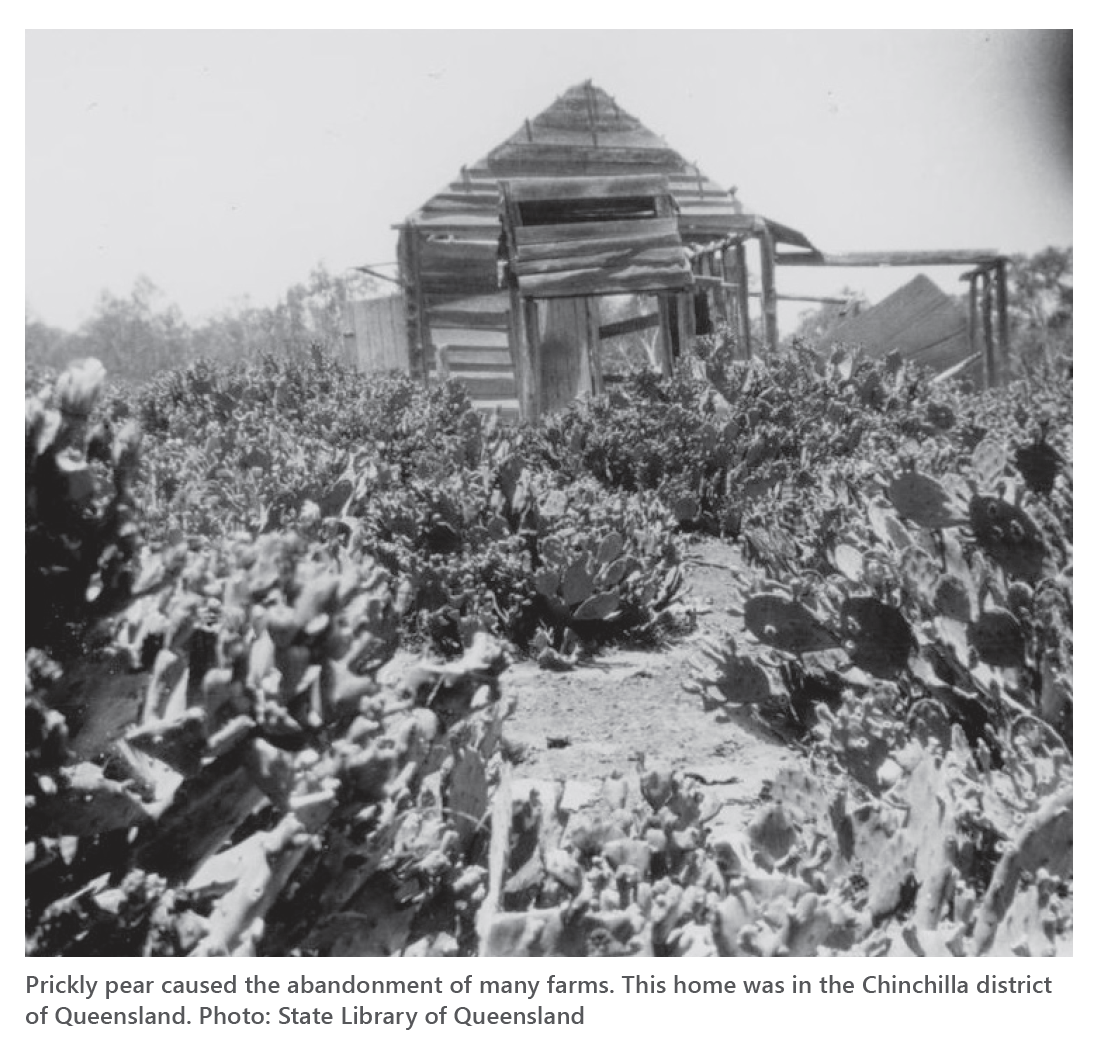

In Australia, the prickly pear was also used as an agricultural fence to divide up stolen land. It thrived in drought-tolerant conditions, displaced native species, and soon covered an area larger than the size of the UK only a few decades after its introduction. After this long invasive and uncontrollable battle with the cactus this “green hell’ was finally controlled with another introduced species, the Cactoblastis cactorum moth. At the same time in India, the East India Company’s cochineal ventures were a different series of missteps and mishaps: from years of failed attempts to get cochineal insects across the sea to the subcontinent, to eventually introducing the wrong species of the insect and producing a lesser quality dye there was no market for, by which time synthetic dyes had also been invented. Their attempts in both locations were a spectacular failure, yetleft lasting impacts on the land and landscape.

-

Correspondence

26 July 2023 7:14am (mex)

Dear Maddy and Keg,

Thank you Maddy for introducing us and pairing us for this exchange!

Keg, very nice to meet you through here. I think we have seen each other in one of FAR’s metings long time ago.

I’m just finishing some holidays and getting back to all the emails and work mode so will start my research on the Amaranth (and Chenopodium subfamily) in the coming weeks.

Maybe I can start to tell you a bit about why my interest to research this plant:

Amaranth is one of the oldest plants that where domesticated in America. I started to learn about Amaranth, or their relatives Chenopodiums (commonly known as goosefoot), when working in the Milpas (ancient and cutlural agricultural systems that intercrop corn, squash and beans) of Oaxaca and Xochimilco. Many of the weeds that sprout around these plots are wild versions of Amaranth, and they are called Quelites in Mexico. Quelites are used for many delicious recipes like tamales, soups, stews, etc. that I had the luck and honour to learn to cook from traditional cooks and my aunties.

Since 5 years or so I live part time between the Netherlands and Mexico. Last year after the experience of helping out in the milpas and plots of Mexican farmers and kitchens of traditional cooks, I wanted to also learn from agricultural practices in the Netherlands. So I started working on a small scale regenerative farm in the east of Amsterdam, and what a surprise! I found myself picking up some wild Goosefoot. Very excited about this, I wanted to cook with them immediately. After this I started to encounter them all over the place, in sidewalks, in kitchen gardens, in Kassel, in London, they brought me joy and sense of connection, and I have gotten the opportunity to share some of the recipes with different groups of people. A german scientist, friend and collaborator, Claudia Heindorf, who researches about agrobiodiversity, told me that these Goosfoot plants are basically universal, they apear almost anywhere in the world.

A plant so close to my culture is also present in other parts of the world and has been cooked by other cultures. It is highly resilient and spreads wildly as it grows, in stoops, cracks, plots. I feel somehow related to this plant, it is a rebel, a traveler, a wild spirit and also transports me back home when I see it (I kind of want to call it “her” by this point) growing in a random place abroad.

I am looking forward to learning more about this plant, or plant family-sub family, and sharing these findings with you!

Let me know if you see her at some point where you are. Here are some pictures that can help you identify her.

Looking forward to learn about your plant,

Mariana

26 July 2023, 23:52 pm (mex)

Dear Mariana,

Thank you for sharing these stories of the Amaranth. I am very excited about this pairing 🙂

I love the variation in the photos you sent of this wonderful species.

We indeed find her in the cracks of our footpaths and in abandoned lots and fields and all over – here most commonly in the form of Green Amaranth (Amaranthus viridis), White amaranth (Amaranthus albus) and what we call Fat hen (Chenopodium album).

But… we also have Native Amaranth here Amaranthus interruptus R.Br., Amaranthus Mitchellii, Amaranthus Powellii, so could well have been eaten by First Nations people here.

I think the first time I ate it was in the early 2000s when I was living in a housing coop in Tucson, Arizona and we did all the shopping at a big health food place. At this time it wasn’t common/ I’d never seen it commercialised and sold in Australia. These days you can, but mostly at health food stores.

I love that this plant grows between the cracks and can survive in so many different climates and environments. I remember collecting some for a project I was doing from the side of s busy road in the front of an industrial building. It was growing wildly and was huge and happy. The beauty of being adaptable.

The plant I chose is another plant you have a close relationship to – the Prickly Pear. I recently made a work tracing the movement of this plant around the world at the hands of the British. I was specifically looking at how they introduced the prickly pear into Australia (where I am a settler) and India (my ancestral lands). They were trying to compete with the colonial Spanish monopoly on the cochineal dye industry.

In Australia by the 1920s it overtook a land mass area larger than the size of the UK (it was known as the ‘Green Hell’). In India they tried and tried to get the cochineal insects over to populate the nopalries they planted but they kept failing in their attempts.

I find it curious that in Australia when it was covering that huge area it wasn’t used as a viable food source. I feel a big part of this was the English attitude to what they thought food was. An early colonist, WIlliam Dampier wrote about Australia ‘the earth affords them no food at all’ when looking around, but Aboriginal people here had thriving agriculture, and a wide range of food harvesting, collecting and hunting techniques. By other accounts, it was plentiful – just not to his eyes…

The prickly pear overran farms and people were abandoning them. Re-colonizing the land. After trying a bird cull, poison, hacking, mulching and all sorts of attempts they eventually introduced the Cactoblastis cactorum moth from Argentina and bred the moth and distributed it to farmers who attached paper tube full of the larvae to the cactus and let them do their work. It eventually controlled the spread. In Australia in many states it is illegal to propagate it or sell prickly pear.

I’ve attached some archival images of the spread.

I look forward to continuing our conversation!

Keg